Introduction

As I write this post, we’re 2 days into a government-imposed lockdown, due to the outbreak of the COVID-19 strain of the Corona virus. All but essential travel is proscribed, and supermarket shelves are empty.

Clearly, those of you reading this within a few months of my writing will know all too well what that’s like – the wall-to-wall news coverage of this story and nothing else, the pictures of still-busy trains and sometimes other locations, with worried and disapproving comments about people “not taking it seriously”, and the war-time-like rhetoric being employed by the government and media.

But, this is a new blog – the idea of which is that these resources and articles will stay here for months or years as a resource for our members. Memories will fade, and the little context provided above will serve to show why this topic seems so relevant right now for an article.

The Dig for victory campaign

Perhaps the most well-known instance of everyone pulling together, large and small, young and old toward a common agricultural goal was the British World War II effort, under the headline of “Dig for Victory.”

I have to admit that – at the risk of showing my ignorance – what I said in the paragraph above was a conception that I had – it was a British thing, and that it came about in the second world war. In fact the idea of persuading the population to do their bit in producing food was established in the first world war, and is an idea whose popularisation probably originated in Canada, under the slogan “A vegetable garden for every home.”

The idea was the same as the familiar British “Dig for Victory” campaign, and was startlingly successful – by the 1944 there were over 200.000 so-called “victory gardens” in Canada.

It’s striking that the production of additional food was, even then, only part of the reason for the campaign. We hear lots these days about “behavioural nudging” (the government has a “nudge unit” which looks at behavioural science and how it can be harnessed to encourage the population down a particular path) and it’s tempting to think that the use of such psychological tools is very much a modern phenomenon, but according to The Canadian Encyclopedia:

Though originally intended as a means of increasing production during wartime, victory gardens proved more important as a symbolic, patriotic activity rather than a productive one. From a morale standpoint, victory gardens linked a wholesome and familiar form of domestic labour to the larger war effort in a way that involved the entire family and that was highly visible to friends and neighbours.

Of course, we’re all familiar with the posters, such as the one above, imploring us to do our bit. However, just as today, every available medium was used to deliver the message. There were the posters, but also adverts in newspapers and, in what was, I suppose, the equivalent of today’s YouTube and Facebook ads, Pathe news films at the cinema:

For the government, this Dig for Victory campaign was deadly serious. There were, as described above, psychological advantages of having everyone contribute. There was continuity of food supply, replacing the pre-war sources of nutrition, many of which came from the countries which had formed the British Empire, with sources which couldn’t be so easily disrupted. And every ship which no longer had to carry food could be re-purposed into carrying people and munitions.

A fascinating article in The Journal of Historical Geography goes further, claiming that it amounted to “an attempt to extend order into the domestic sphere.” I’m not sure that that case is proven, but the article does provide lots of detailed examples of how the campaign was created and pursued with military vigour and determination – if not always precision.

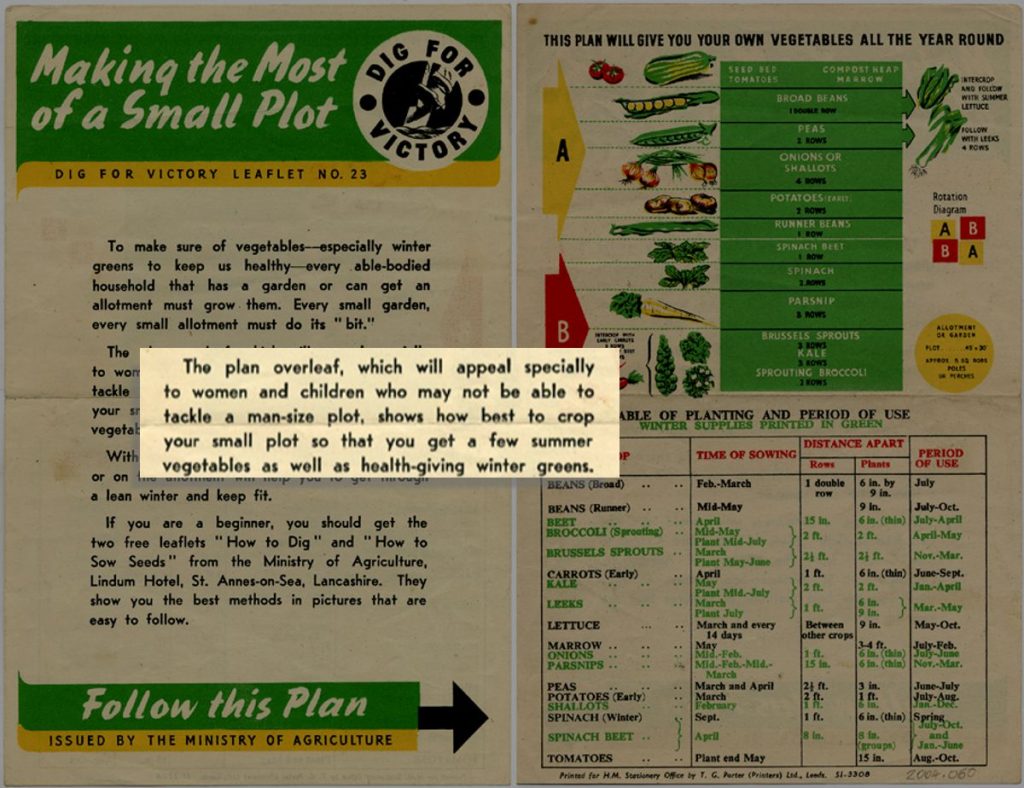

The main aim of the campaign wasn’t to simply encourage more veg planting, but to ensure a robust, continuing supply of food. To that end, there were long debates within government about exactly which vegetables should be grown – minutes from the Horticultural Advisory Council show just how fascinating these debates must have been (for those who didn’t have to attend them, at least!):

In section A also it was decided that spinach should be replaced by spinach beet sown in the Spring. The true spinach should be inter-planted in Section B. A suggestion made by Sub-committee 3 at the meeting on 14 July that the crops of peas, broad beans, etc, should be increased to occupy at least one-tenth of the area of the allotment was discussed and it was decided that peas should be increased to four rows.

It is, perhaps, a shame that having put so much thought into exactly what should be grown, when, where and how, little errors crept in to some versions of the final leaflets which were distributed, such as suggesting to the new army of unsuspecting gardeners that marrows should be planted 3 inches apart, rather than three feet…

Rather like looking through an old newspaper, and finding that the adverts are often more interesting than the news, these leaflets also show a fascinating glimpse into the more patrician nature of life at the time:

Did the campaign work?

So ingrained is the Dig for Victory campaign within our national consciousness that it would seem that this is an obvious “Yes!”. But it may not actually be as clear cut as that.

During the war, the government commissioned a series of reports, based on interviews with the general public. These were known as the Wartime Social Surveys, and dealt with whatever issues the government wanted feedback on – from the “location of dwellings in Scottish towns” to – you guessed it – in Survey Number 20, carried out in 1942, “Dig for Victory”.

The survey’s results seem a little patchy and inconsistent, but one can only imagine the disappointment in the Ministry of Agriculture on hearing that, when asked what government publicity they’d seen, only 34% of gardeners mentioned “Dig for Victory”. Only ten per cent of gardeners said they’d used the campaign’s “Cropping Plan” to guide their cropping, compared to 70% who said they relied on information on the radio.

As a side note, the BBC had, since 1931, broadcast “Mr Middleton’s ‘In Your Garden'”. The Mr Middleton in question (C. H, Middleton) was such as figure of authority that he was chosen by the government to be the face of the Dig for Victory campaign.

In a very early instance of the BBC interacting with its audience, he asked his listeners to write in to give their preference as to the time slot for the show – which over 10,000 of them did!

Nonetheless, whilst the government’s vision of a population growing those vegetables deemed most appropriate by “the Ministry” may not have been fulfilled, in a wider sense the campaign clearly did work. The Wartime Social Survey reported that in every social class, people were growing more vegetables than before the war:

Class and wartime vegetable cultivation

| Amount of vegetables grown | Unskilled manual | Skilled manual | Unskilled clerical | Skilled clerical |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Same as before war (%) | 53 | 43 | 39 | 32 |

| More than before war (%) | 47 | 57 | 61 | 68 |

Source: Wartime Social Survey, Dig for Victory: a study of the impact of the campaign to encourage vegetable growing in gardens and allotments, for the Ministry of Agriculture, 1942

Furthermore, the fact that this is still, 80 years on, one of the most widely remembered campaigns of the second world war shows its lasting impact.

Would any similar campaign today gain anything like that traction? There’s no sign as yet of the government instituting any modern equivalent campaign in the light of COVID-19. That’s understandable, of course – we all hope that the outbreak will have effects that last much less than the time it takes to grow a decent crop of beetroot or swede. And, it takes time and space to grow anything – all elements in perhaps shorter supply today than in 1939.

But I do wonder if a trick is being missed. Supermarket shelves are empty, but they’ll re-fill. At that point, people will go back to buying food from all over the globe. And the chance to have instilled a generation with the enthusiasm to get out and start something growing, get a seedling nurtured that will eventually land with a thud on the table may have been lost.

I for one will be starting construction on the new veg garden this very week end. It’s been long-planned, but this crisis has given it new impetus. If it works, you’ll see me in the SFTG meetings this autumn with my crop for sale! If not, you’ll still see me there, but probably on the other side of the veg-sales table…

Links to resources mentioned above:

Here’s the full Dig for Victory “Making the most of a small garden” leaflet